By Farshid Rafiei

The South-Central Foundation, an independent health authority responsible for the health and wellbeing of 65,000 Native Americans throughout the state of Alaska, was established back in the mid-1980s. This was a time when our own federal government still controlled not only operating budgets for healthcare services on First Nations reserves, but also ‘designed’ and delivered the built infrastructure these services required.

The South-Central Foundation healthcare system is based on a holistic approach to treatment that, rather than responding to the visible symptoms a patient presents at a one-on-one consultation with a doctor, uses a multidisciplinary team-based approach to uncover the underlying causes behind a patient’s medical condition. This approach resonates with the holistic view most Aboriginal people have regarding the relationship of the individual to family, community and more broadly to nature.

While the rules around the design of healthcare facilities on First Nations reserves in Canada changed in the late 1980s, changes to the delivery model for healthcare services took much longer. The First Nations Health Authority (FNHA) with provincial jurisdiction was established in British Columbia in 2013 and only now is the traditional service delivery model being re-examined and reinvented to better suit the needs of Aboriginal communities.

Gone is the clinical model, by which a patient accessed a physician in an institutional environment – the typical sequence being a stark waiting room with upright chairs lining the walls; a reception counter with a sliding glass panel at which one stands and delivers personal information; a long walk down a grey and featureless corridor; a hurried conversation with a white-coated doctor in a small and windowless consulting room; and the usual result – walking away with a prescription to fill.

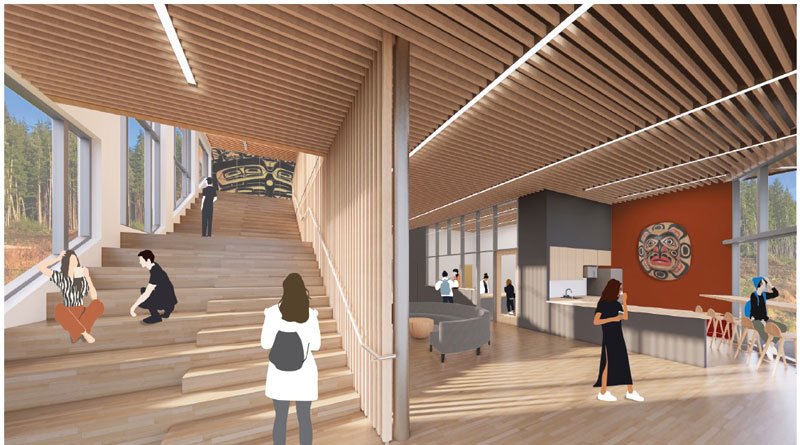

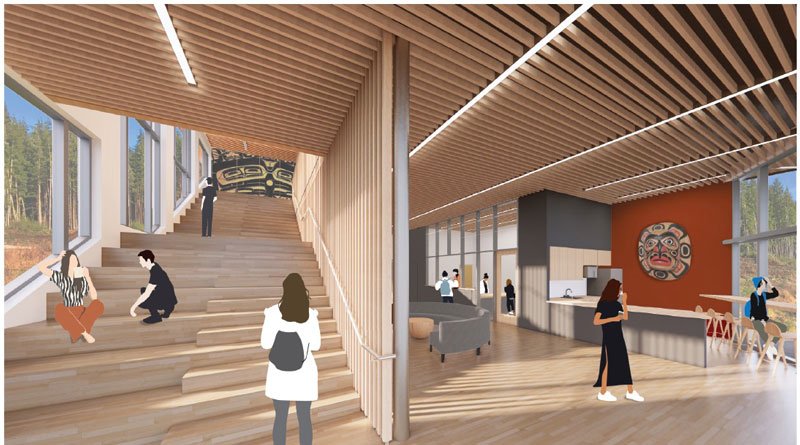

In its place comes a very different healthcare experience in which architecture plays a significant role, by interpreting community needs and cultural values, while acknowledging the social sensibilities and stigma that may surround the act of accessing health services.

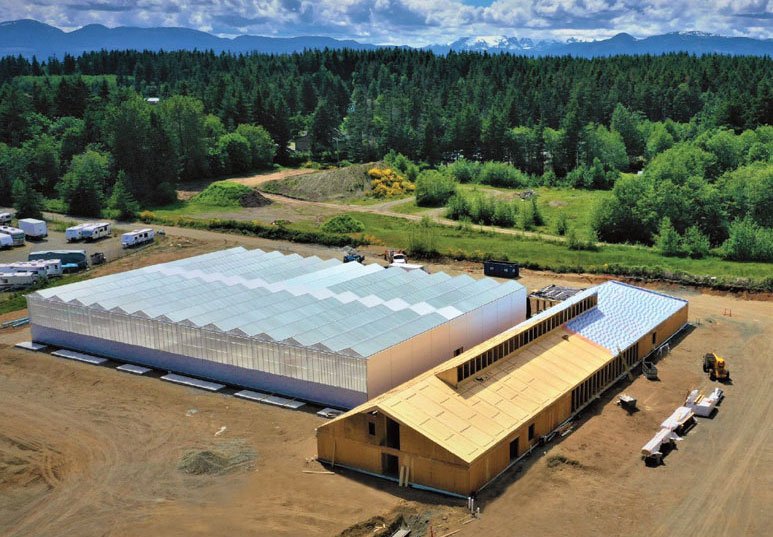

Under construction in the magnificent and expansive archipelago of Haida Gwaii (population 5,000) is the Skidegate Health and Wellness Centre, which not only creates a very different physical environment for healthcare services, but also an emotionally supportive one.

Skidegate itself has only 900 inhabitants, so privacy can be hard to come by and rarely does a visit anywhere (never mind to the doctor) go unnoticed. Young adults in particular are sensitive – and to some degree secretive – in this regard, preferring that their parents do not discover they may be struggling with substance addiction, or mental health challenges.

However, in Haida culture, where respect for Elders remains strong and the matriarchal structure of society places grandmothers, in particular, in a position of trust, influence and power – these same young adults are much more comfortable sharing personal information with them.

Equally important in its influence on the design, the Haida place enormous importance on their association with and proximity to the ocean, and favour buildings that offer a sense of openness and connection, rather than enclosure and confinement.

We have approached the design of the Skidegate Health and Wellness Centre with this physical and cultural context in mind. On the side of a hill overlooking the ocean, the building follows the slope rather than the contours running across it, enabling all public areas and frequently occupied private spaces to have a view of the water. The road to the Health and Wellness Centre extends a little further to another building – an Elders housing complex.