Deep green retrofit demonstrates a ‘smart’ model for scalable energy and carbon reductions

By Charles Marshall, Gerry Doering, Bahaa Al Neama, DIALOG

Deep green retrofits represent a critical component of the building industry’s response to climate change. Mobilization across the public and private sectors is necessary to meet national targets for carbon reduction. This project represents a visionary and scalable model for how private buildings can be retrofitted to save energy, reduce carbon, and increase community wellbeing through healthy building strategies and public realm enhancements.

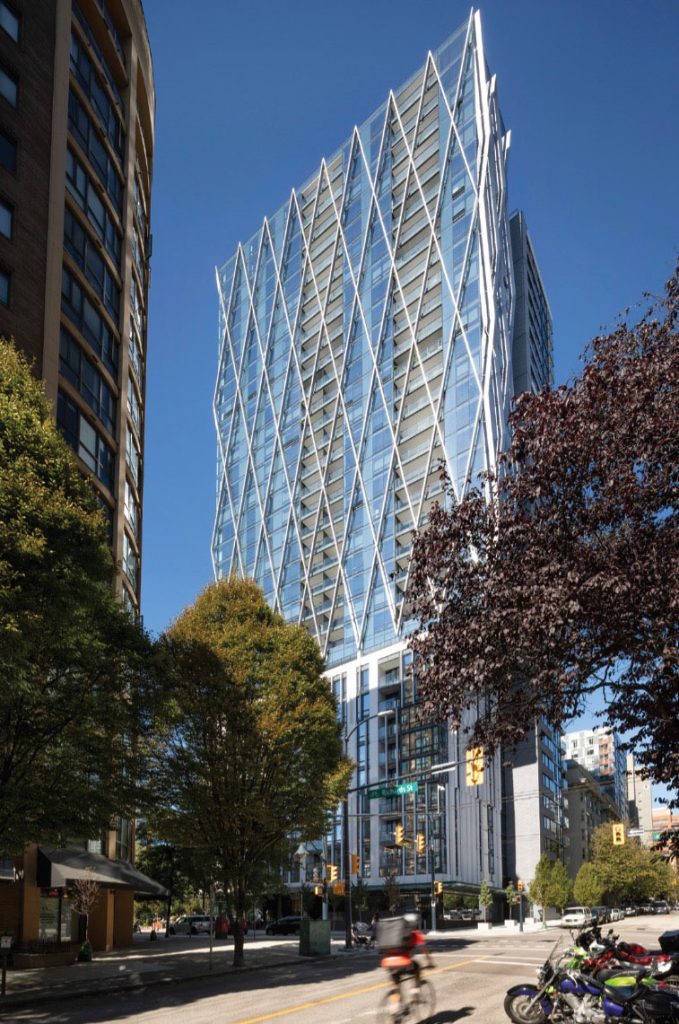

HSBC Bank Place occupies a prominent corner in downtown Edmonton at 103rd Avenue and 101st Street. The building was originally constructed in 1980. By 2017, although the tower still demonstrated some excellent qualities, including excellent urban connectivity and a structure that was built to last, the property was ready for re-investment.

During the initial planning and investigation phases, it was determined that the property was a great candidate for a revitalization and deep green retrofit. Integrated workshops and collaboration between owner, developer, contractor and the design team revealed that an ambitious project scope including re-cladding, replacement of major building systems, and the integration of ‘smart’ building controls could save substantial energy and carbon while materially increasing the property’s attractiveness to tenants.

Across Canada and globally, the need to rapidly reduce GHG emissions creates a strong imperative to decarbonize the buildings sector. This project provides a unique and inspirational model for how this can be accomplished in a commercial context, demonstrating that there is a business case for healthy, low-carbon, and intelligent ‘smart’ buildings.

RETROFIT STRATEGIES

The revitalization project included a complete re-cladding of the tower with the installation of a new, thermally broken triple-glazed curtainwall system and associated upgrades to other building envelope sections. This envelope replacement dramatically improved thermal insulation values, reduced air leakage, increased occupant comfort, and reduced heating and cooling loads.

HVAC systems were completely replaced, with an old inefficient overhead VAV system giving way to a new dedicated outdoor air system connected to local fan coil units with demand-controlled ventilation. Lighting was replaced with new high-efficiency, all-LED fixtures connected to advanced controls for occupancy and daylight modulation.

Technology also plays an important part in the strategy for repositioning, revitalization, and targeting of deep reductions in energy, GHG, and utility expenditure. Systems that are typically separated, including HVAC, lighting, access control, building management, intercom, and video, were connected to an integrated backbone and delivered as one single solution. The result is a highly intelligent building with smart systems for security, communications, tenant experience, and energy tracking. Tenants can access amenities such as parking and the wellness centre using only their cell phones. In 2020, the project was awarded a WiredScore Platinum certification.

The project scope also included a renewal of the streetscape and landscaping, replacing the aged exterior and minimal public realm with planters, furniture, and space dedicated to socialization and relaxation. The specific context, opportunities, options, and outcomes for the project were evaluated through a lens of community wellbeing, seeking goals and measures that could provide impact outside of the project site area and contribute to the rejuvenation of the downtown.

The result is a property that is completely revitalized and repositioned in the local marketplace. Higher ceilings, more daylight, improved temperature control, and better ventilation air quality contribute to a healthier work environment and position the property to compete with new, modern office towers in downtown Edmonton.

Project Team

- Owner Alberta Investment Management Corporation (AIMCo)

- Asset Manager and Property Manager Epic Investment Services

- Development Management Cushman Wakefield Asset Services

- Architect, Interior Designer, Landscape Architect, Sustainability Consulting, Building Performance Analysis DIALOG

- General Contractor PCL Construction Management Inc.

- Structural Engineering RJC Engineers

- Mechanical & Electrical Engineering Smith + Andersen

- Commissioning & Building Envelope Morrison Hershfield

SUBSCRIBE TO THE DIGITAL OR PRINT ISSUE OF SABMAGAZINE FOR THE FULL VERSION OF THIS ARTICLE.