One Planet Living project one step in reclaiming former industrial site

By Figurr Architects Collective

Located in both Ottawa and Gatineau, the Zibi development aims to be transformative physically, environmentally and socially. The only One Planet Living endorsed community in Canada, Zibi occupies formerly contaminated industrial lands, and is transforming them into one of Canada’s most sustainable communities. Incorporating public spaces and parks, as well as commercial, retail, and residential uses, Zibi will be an integrated, carbon neutral mixed-use community, one that’ll help reinvigorate the downtown cores of both Ottawa and Gatineau.

Complexe O, located on the Gatineau side of the Ottawa River, is Zibi’s first mixed-use building. It arose from the desire to create a socially responsible project that would set a precedent for future development. The project takes its name from the word ‘eau’ (water) as it offers residents a panoramic view of the Ottawa River and the Chaudière Falls. The six-storey Complexe O building includes a range of housing from studios to two-storey mezzanine units, as well as commercial space on the first floor.

The location is significant; as under the ownership of Domtar (whose paper mill closed in 2007) the land had been inaccessible to the public for nearly 200 years. Now cleaned up and revitalized, the riverbank is once again available to the residents, not only of Complexe O, but all of Gatineau.

The architectural program is based on the ten principles of One Planet Living, one of the broadest frameworks for sustainable development, which sets a range of measurable goals. The fundamental principles guiding the construction of Complexe O are the use of carbon-neutral heating and cooling and sustainable water management. The project has achieved LEED Silver certification.

Carbon neutral energy is supplied from the Zibi Community Utility, a district energy system relying on energy recovery from effluents of the nearby Kruger Products Gatineau Plant for heating, and the Ottawa River for cooling. All the apartments in Complexe O are fitted with Energy Star certified appliances; LED lighting has been used throughout the entire building, including first floor commercial units and amenity spaces; and generous glazing reduces the need for artificial light.

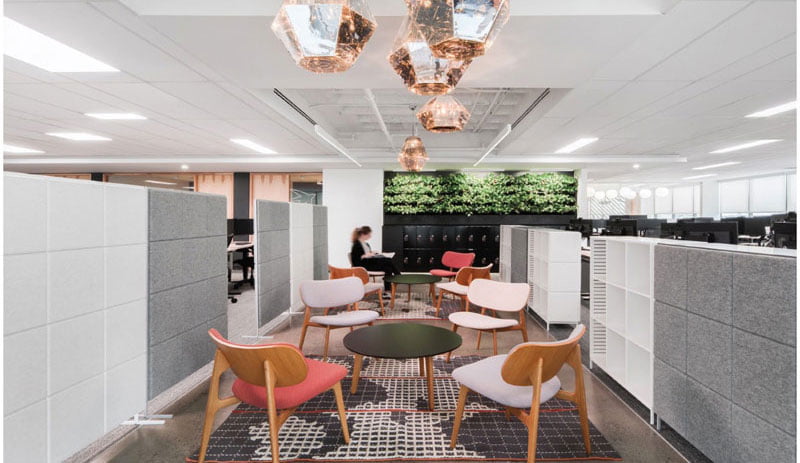

The commercial space on the first floor is leased primarily to local and socially-responsible businesses, enabling residents to shop for essentials without having to rely on transportation. n addition, the central location in the heart of Gatineau is served by numerous bus lines from both Gatineau and Ottawa offering hundreds of trips per day.

This connectivity contributes to the Zibi development goal of a 20% reduction in carbon dioxide associated with transportation as measured by the car-to-household ratio. While the rest of the province has a 1.45 car to household ratio, the residents of Complex O have reduced this to 1:1. In addition all parking spaces are designed to accommodate electric charging units.

The project is located right on the Zibi Plaza, in fact forming one wall of the plaza, which offers residents a quiet and relaxing outdoor space that is closed to vehicular traffic but crossed by a bicycle path. Art exhibits are held in the vicinity to support local artists and artisans. Complexe O also provides residents with 15 garden boxes; gardening being an effective way to foster community.

PROJECT CREDITS

- Architect Figurr Architects Collective

- Owner/ Developer DREAM / Theia Partners

- General Contractor Eddy Lands Construction Corp.

- Landscape Architect Projet Paysage / CSW Landscape Architects

- Civil engineer Quadrivium

- Electrical Engineer Drycore 2002 Inc. / WSP Canada Inc.

- Mechanical Engineer Alliance Engineering / Goodkey Weedmark & Associate Ltd.

- Structural Engineer Douglas Consultants Inc.

- Other consultants BuildGreen Solutions, Morrison Hershfield

- Photos David Boyer

ONE PLANET LIVING

One Planet Living is based on a simple framework which enables everyone – from the general public to professionals – to collaborate on a sustainability strategy drawing on everyone’s insights, skills and experience. It is based on ten guiding principles of sustainability which are used to create holistic solutions.

• Encouraging active, social, meaningful lives to promote good health and wellbeing.

• Creating safe, equitable places to live and work which support local prosperity and international fair trade.

• Nurturing local identity and heritage, empowering communities and promoting a culture of sustainable living.

• Protecting and restoring land for the benefit of people and wildlife.

• Using water efficiently, protecting local water resources and reducing flooding and drought.

• Promoting sustainable humane farming and healthy diets high in local, seasonal organic food and vegetable protein.

• Reducing the need to travel, encouraging walking, cycling and low carbon transport.

• Using materials from sustainable sources and promoting products which help people reduce consumption; promoting reuse and recycling.

• Making buildings and manufacturing energy efficient and supplying all energy with renewable.

FIGURR ARCHITECTS COLLECTIVE HAS OFFICES IN OTTAWA & MONTREAL.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE DIGITAL OR PRINT ISSUE OF SABMAGAZINE FOR THE FULL VERSION OF THIS ARTICLE.