Residential (Large) Award (Sponsored by Inline Fiberglass)

Public Architecture + Communication

Jury Comments: Not only does Passive House certification take this building beyond Code in terms of energy performance; it achieves this while still addressing issues of context and community. The relationship to its surroundings is carefully considered, as is the design an organization of its common spaces. Making successive cohorts of students aware of the superior quality of a Passive House environment – and so raising their expectations, may be the most significant contribution of this project.

This new Passive House certified residence accommodates 220 students within five floors of light wood frame construction, above a concrete ground floor that contains common areas, amenity and service spaces. The building completes an ensemble of residence buildings encircling the central green space on campus – known as Commons Field.

The five identical residential floors include shared bathrooms flanked by two bedrooms. This layout allows space for quiet study when required. Additionally, each floor contains both a study lounge and a house lounge with views of the surrounding mountains, the latter equipped with a kitchenette, dining table and couches. Locating these spaces at opposite ends of the floor ensures that quiet study is not interrupted by noise from the social home lounge.

The first level includes a large laundry room adjacent to the student lounge. Separated by a glass wall, the relationship between the two spaces encourages chance meetings and spontaneous gatherings. Moreover, the transparency offers passive surveillance, or visibility that promotes a sense of security.

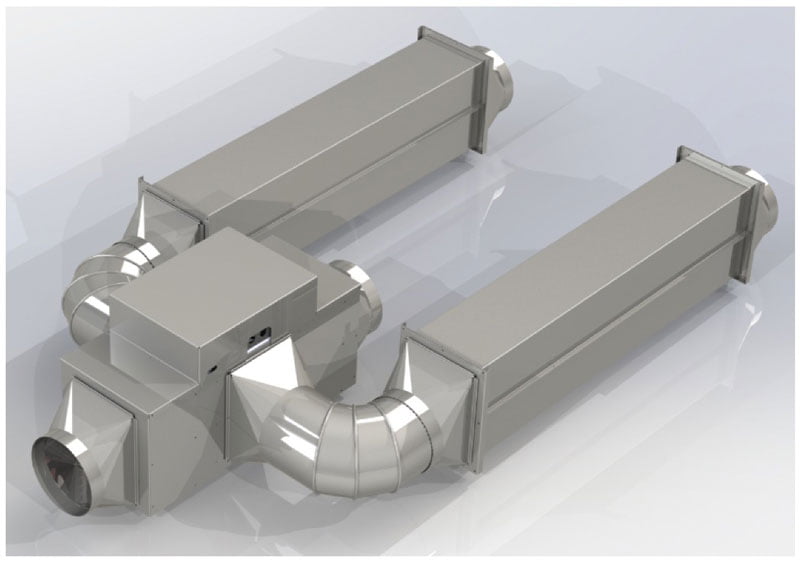

The Passive House goal of minimal energy use for heating and cooling informed many design choices. Given that irregular forms with multiple indentations and corners, or projections such as steps, overhangs, or canopies create challenges for insulation, airtightness and the elimination of thermal bridging, a simple and efficient rectilinear volume performs best.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE DIGITAL OR PRINT ISSUE OF SABMAGAZINE FOR THE FULL VERSION OF THIS ARTICLE.