From industrial site to residential living, condo uses exterior corridors to save energy

From industrial site to residential living, condo uses exterior corridors to save energy

This six-storey, 5,040 m², residential condominium building at 25 Ritchie in Toronto is located on what had been an industrial site for more than 100 years. Consequently, the land required exstensive remediation prior to redevelopment. The adjacent properties in the small triangular-shaped city block are a mix of single-family residential and industrial uses.

By David Anand Peterson

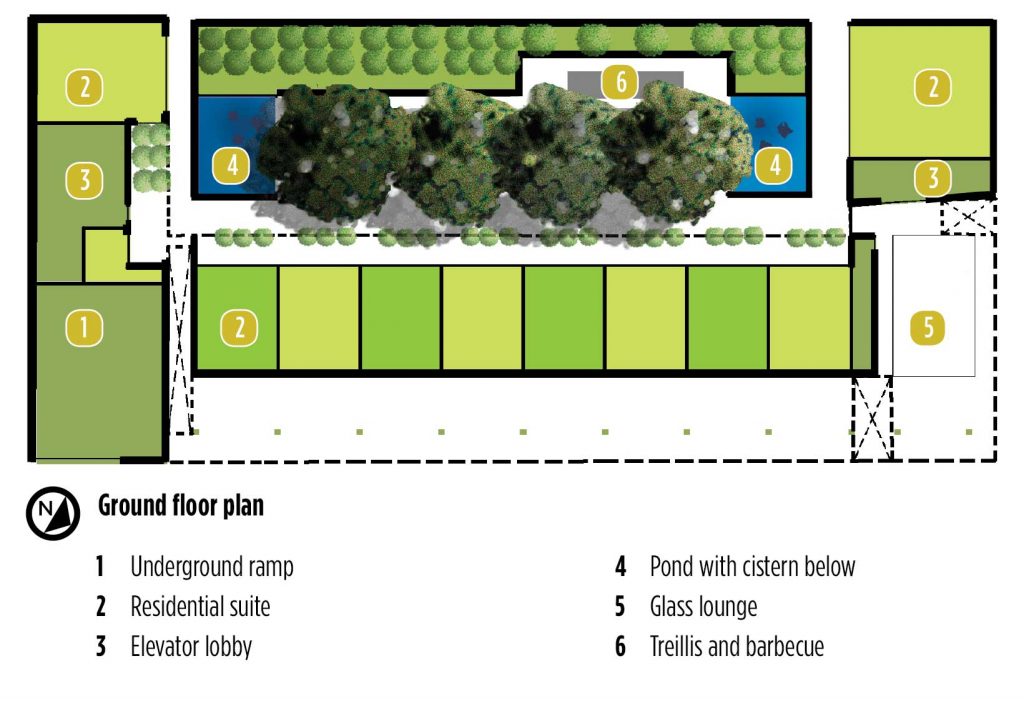

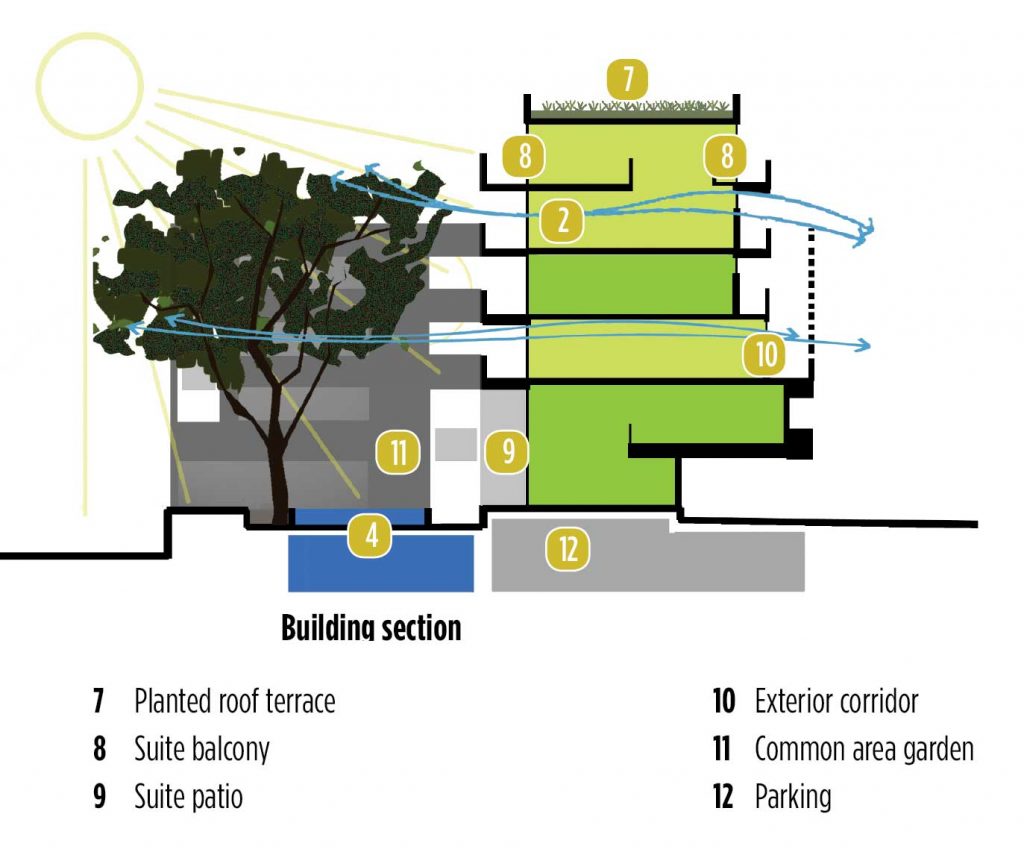

The configuration of the building addresses this disparate context, with the southwest-oriented courtyard facing the residential back yards. The courtyard is characterized by trees and planting which shade the building and reduce solar heat gain. Century-old oak trees in the neighbouring residential properties perform the same function. Within the courtyard, the removal of contaminated soil and its replacement with a nutrient-rich variety, together with the planting of native honey locus trees, returns the land to its pre-industrial condition.

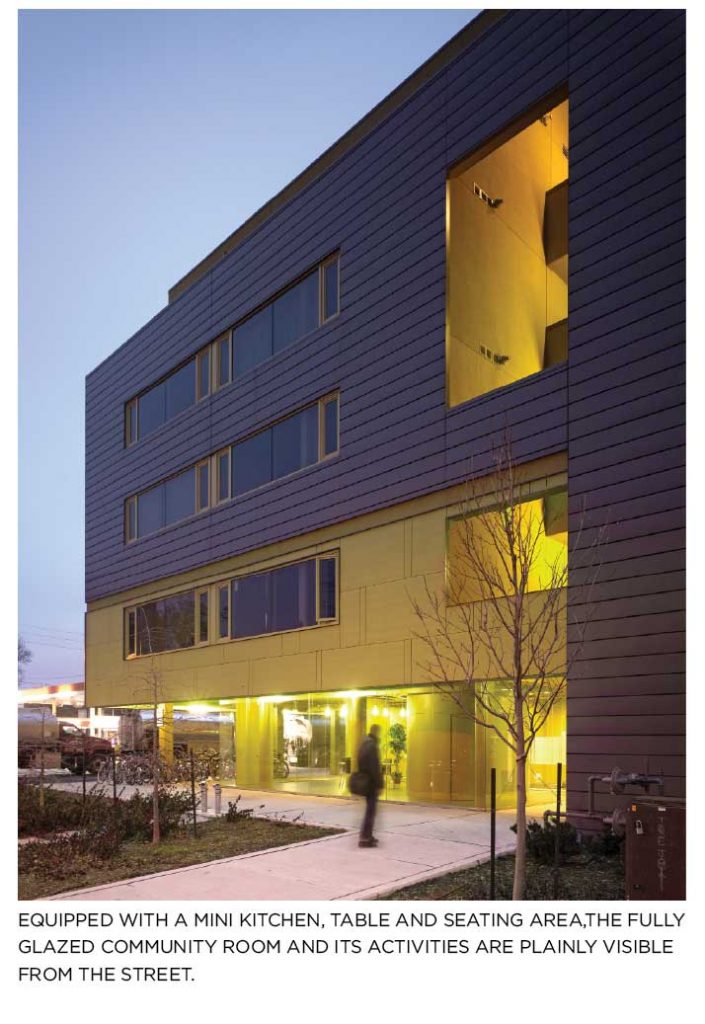

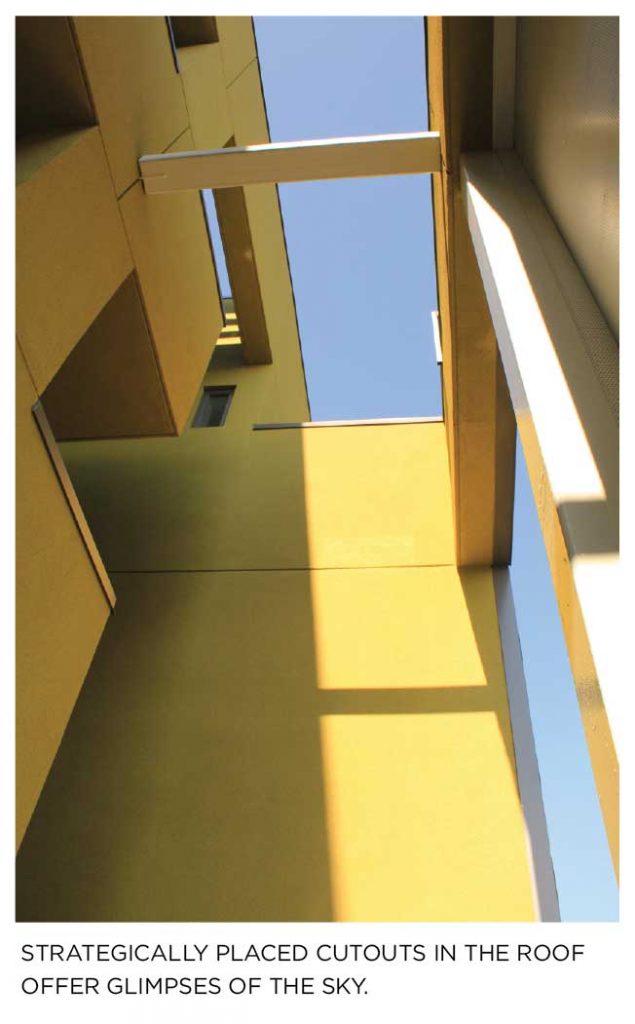

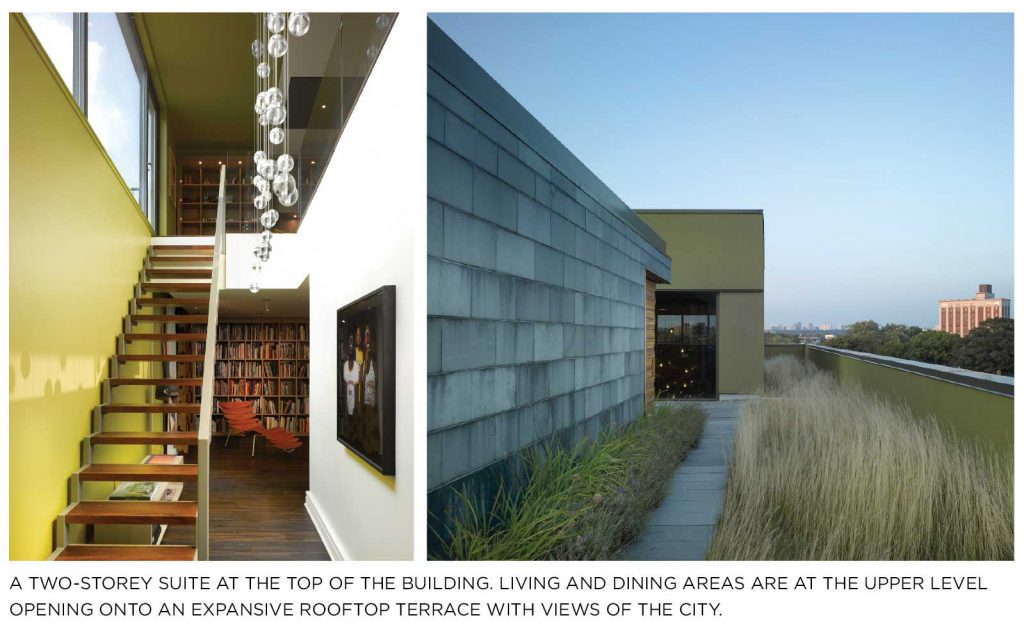

To contend with the site’s industrial edge, the building employs single-loaded corridors, which wrap the outside of the C-shaped form. These corridors are the buffer between the residential units and their noisy industrial neighbours. Metal cladding, recalling the site’s industrial past, is carved and perforated, opening the corridors in varying degrees to the exterior.

With our inclement weather, exterior corridors may seem like an unusual design choice at first. However, the residents at 25 Ritchie are representative of a new urban population who choose to walk, bike or take transit in all seasons. As such, they dress for the weather before leaving their suite, and the exterior corridors provide a transitional micro climate between indoor and outdoor conditions.

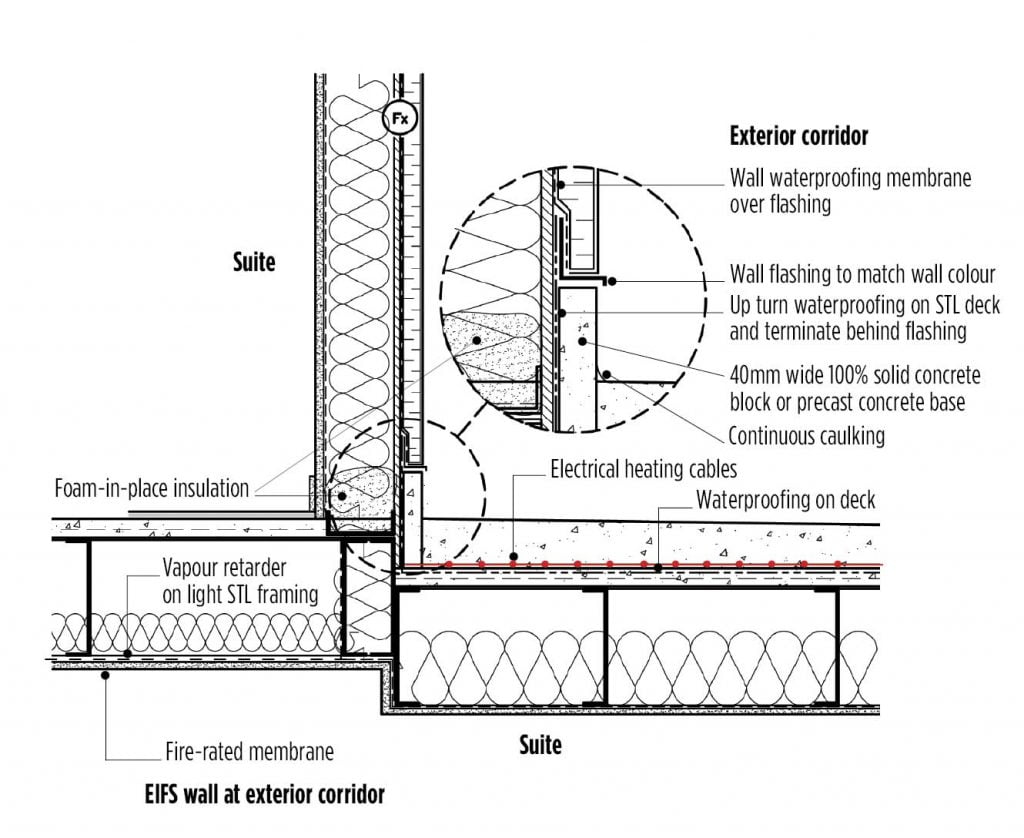

The snow and ice common to Canadian winters are managed by heating cables embedded in the concrete floor and activated by sensors as required. Compared to conventional interior corridors, the external corridors use very little energy as no space heating or cooling is required. Being naturally lit for much of the time, they also reduce the energy required for artificial lighting.

In addition to reducing energy demand, the exterior corridors also reinforce the connection between the residents and the neighbourhood they live in. The design goal, both for this project and for our architectural practice, is to express the sustainable design choices we make in a poetic and engaging way. An example of this approach is the design of the two underground rainwater storage cisterns. All roof drains and catch basins direct their water to the cisterns which are sized to contain a five-year storm event.

In essence, every drop of rain is stored. This stored water helps to reduce the stress on an over- taxed combined sewer.

PROJECT CREDITS

- Client Triumph Developments

- Architect David Peterson Architect

- Construction Manager Triumph Developments

- Structural Engineer Blackwell Bowick Partnership Ltd.

- Mechanical Engineer Norlin Engineering

- Electrical Engineer Mitra Consulting

- Stormwater Management Trow Consulting

- Code Consultant Hine Reichard Tomlin

- Cost Consultant Pelican WoodCliff

- Photos Ben Rahn of A-Frame

MATERIALS

- – Light-steel framing with stucco finish, perforated metal cladding applied in various places to the open exterior corridors

- – Batt insulation in exterior walls with exterior layer of rigid foam insulation to mitigate thermal bridging

- – In-floor heating for exterior corridors

- – Vegetated roof

- – All rainwater flows to underground cisterns sized to contain a five-year storm event

David Anand Peterson, B.Arch, Dip.Arch.Tech., OAA Principal of David Peterson Architect Inc. and Adjunct Professor of Architectural Technology, Sheridan College.