Designing Interior Environments

that Support Human Health

Although we have known for a long time that Canadians spend over 90% of their time indoors, only recently have we consciously begun to design environments that not only meet health and safety regulations, but also actually improve occupant health and wellbeing.

By Kaitlyn Gillis and Michelle Biggar

The idea of ‘sustainable design’ has been central to architectural discourse and practice for more than 20 years. In the original definition of sustainability, we were encouraged to consider economic, environmental and social impacts. However, in practice, we have focused most of our attention on the environmental and economic aspects of sustainability and neglected the social implications of design.

This situation is changing, and issues relating to physical and mental health, as well as social and cultural considerations, are being re-introduced into the conversation. Thus architects and interior designers now face the challenge of embracing this more holistic approach to design; an approach that puts people at the centre of the process.

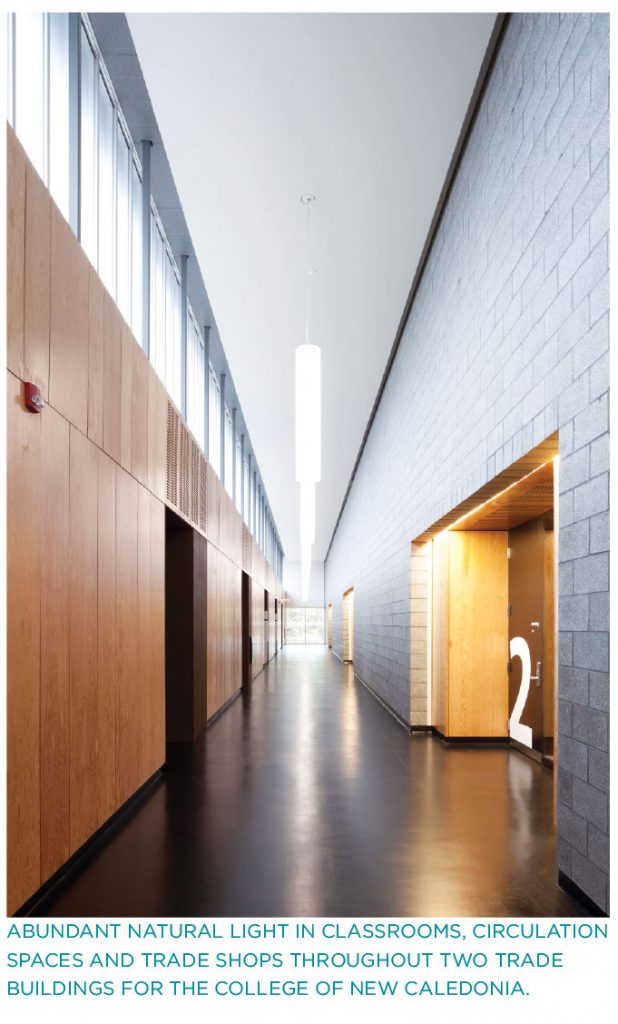

People-centred design intertwines a number of related strands of research, including biophilia, active design, the effects of lighting on circadian rhythm and the adaptability and livability of spaces. This article explains these aspects of design and illustrates them with examples from the work of the Vancouver-based Office of Mcfarlane Biggar Architects + Designers [OMB].

Why human health and wellbeing?

As defined by the World Health Organization, human health is, “… a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” Our wellbeing depends on many factors, including our biological make-up, our experiences and our interactions with our environment. When we speak about health and wellbeing, the implications extend far beyond simple employee productivity – although for many years, this has been the sole metric by which we have measured occupant health.

While the marketplace may have struggled to quantify the other benefits of designing for people, these have long been a subject of academic research in the field of environmental psychology. To continue to focus only on productivity limits the value of the discourse and ignores the diversity of people that use, and are affected by, the multitude of different building types they experience.

As an example, for a traveller passing through an airport, a ‘healthy’ space will be one that creates a calm and reassuring environment, so relieving the stress that is often associated with travel. By contrast, for a worker in an office, it is productivity [or to use a better metric, performance], that makes a difference to their organization’s bottom line.

Kaitlyn Gillis has a Bachelor of Engineering in Building Engineering; Master of Science in Architecture: Advanced Environmental and Energy Studies; and a Master of Science in Environmental Psychology. She is Project Manager, Light House Sustainable Building Centre in Vancouver. Michelle Biggar, NCIDQ, LEED CI is a principal at Mcfarlane Biggar Architects + Designers in Vancouver.