Today, it is the task of averting drastic climate change that might be described as an experiment – a vast social experiment in decision-making and democratic action. Success in that endeavor will not be determined primarily by large techno-logical fixes, though many will be needed along the way. Just as decisive to the outcome is whether our social relationships, cultural beliefs, and political customs will allow for the kind of changes that are necessary. That is why the climate crisis is as much a social as a biophysical challenge, and why the solutions will have to be driven by a fuller quest for global justice than has hitherto been tolerated or imagined.

Today, it is the task of averting drastic climate change that might be described as an experiment – a vast social experiment in decision-making and democratic action. Success in that endeavor will not be determined primarily by large techno-logical fixes, though many will be needed along the way. Just as decisive to the outcome is whether our social relationships, cultural beliefs, and political customs will allow for the kind of changes that are necessary. That is why the climate crisis is as much a social as a biophysical challenge, and why the solutions will have to be driven by a fuller quest for global justice than has hitherto been tolerated or imagined.

– Andrew Ross, from Bird on Fire

Finding a way to design the physical and social aspects of a community

By Darryl Condon

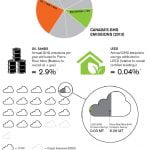

In February of 2015 Royal Dutch Shell announced its decision to cancel its Pierre River oil sands project due to lower global oil prices. Discussion in the media focused on the economic implications, while within sustainability circles, the concern was for the effect lower oil prices have on growth in the renewable energy sector. What is overlooked from a Canadian perspective is that lower energy prices, when they result in cancellation of projects has a positive impact on Canada’s ability to meet GHG reduction commitments.

An inconvenient truth for the green building industry is that the cancellation of a single oil sands project is far more significant than the collective efforts that we have made to reduce emissions through our work. Pierre River was projected to produce 200,000 barrels per day. This equates to over 5 MT of GHG emissions per year; just under 1% of Canada’s total GHG emissions in 2013. This is approximately 150 times the aggregated impact of GHG reductions from LEED Certified buildings in Canada.

The figures [see graphic at right] highlight a startling comparison between the impact of oil sands extraction and the strides made in GHG emission reduction through buildings. While this should not deter one from striving to reduce the impact of our new and existing building stock, it does highlight the relative scale of our impact and the collective challenge we face.

Government of Canada projections make it clear that the GHG impact of our energy extraction sector will far outweigh the conservation efforts made across all other sectors, leading to the conclusion that a broader approach to social and cultural change must occur if our response to the threat of climate change is to be successful.

Much conventional sustainable design thinking is predicated on the assumption that we will be successful in avoiding the impacts of climate change. Many now believe this assumption is no longer valid and that we should work to help communities adapt to the local and regional effects of climate change, whether this be flood resistance, drought, sea level rise or some other phenomenon.

At HCMA Architecture + Design, we believe that we must pursue a broader sustainability agenda that, while remaining committed to continuous improvement in environmental performance, places increased emphasis on the social and physical conditions that will lead to increased societal resilience. We have recognized that the social spaces that bring diverse sectors of the community together are the crucibles of information sharing and trust building – and thus contribute to increased social cohesion, inclusive decision making and action in the collective interest.

A building constructed above the flood plain is an ‘ark’ of sorts that will see some of us safely to the point when the waters subside, but the important question is whether all species [or sectors of society] will be invited aboard.

DARRYL CONDON ARCHITECT AIBC, AAA, SAA, OAA, FRAIC, LEED® AP, IS MANAGING PRINCIPAL OF HCMA ARCHITECTURE + DESIGN, VANCOUVER.