Optimizing flexibility, affordability and construction efficiency

Optimizing flexibility, affordability and construction efficiency

By Michelle Xuereb, Dev Mehta, Adryanne Quenneville and Tiffany Wong of BDP Quadrangle

The world is in a period of increased urbanization. In 2018 the United Nations estimated that by 2050 68% of the global population will be living in an urban area. Urban population growth has driven up land value and the costs associated with residential building construction. For most, living in an urban area means residing in a multi-unit residential building (MURB).

As the costs related to urban residential development have increased, the average unit size has decreased. For example, a typical two-bedroom-plus-den unit in one of Toronto’s older stock of residential buildings is usually around 1,000 square feet. Current residential developments fit the same program into roughly 750 square feet.

This squeezing of the floor plans, however, has reached its breaking point. Residential units can only be tightened so much without sacrificing the quality and functionality of the space. When every room is competing for floor area, designers need to get creative.

In March, BDP Quadrangle held a studio-wide ‘Shrinking Spaces Charrette’ to come up with innovative solutions for small units. We took a typical residential unit apart – examining every inch of space from the master bedroom to the pantry shelf – to find creative new ways of maximizing square footage within a limited space.

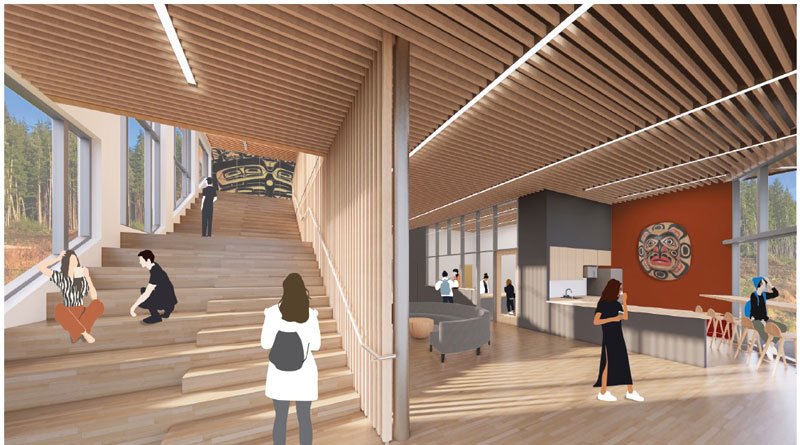

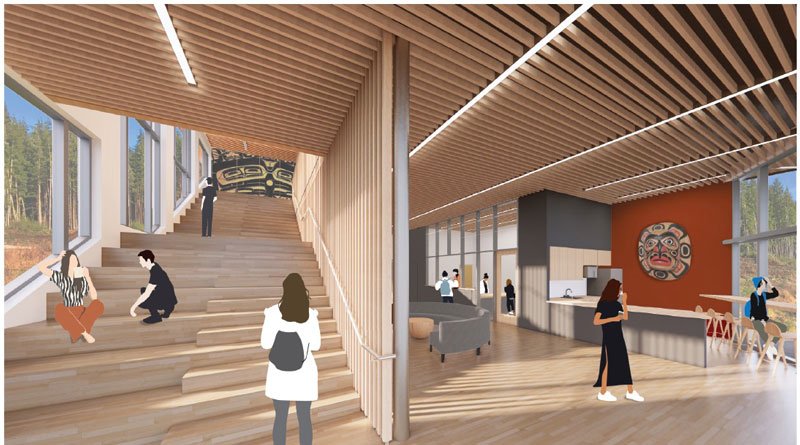

The future MURB unit does away with fixed rooms with set programs. Isolating in response to the pandemic has prompted all of us to find more flexibility in our living spaces, and also to question how MURB design can go further to support a sense of community and foster interaction with others while still maintaining privacy and a safe distance if required.

This pandemic experience has equipped us with a direct and immediate understanding of the specific desires for an improved at-home wellness experience – such as a need for both togetherness and separation from other family members; having a place to stow away a computer at the end of the day; the possibility to grow vegetables on a balcony; and the benefit of socializing with neighbours. We identified a need for more resilient, sustainable, flexible, and healthy spaces – all within a small footprint in order to maintain an affordable unit.

We began rethinking MURB units by asking: what would happen if we reduced or eliminated set programs? In order to optimize flexibility, we propose blurring the lines between rooms, rather than delineating them with demising walls.

To accommodate this, the building is designed with a structural column grid instead of shear walls, as is typical of Toronto construction. This structural system also uses less concrete – thereby reducing the building’s carbon footprint. For other elements that are typically fixed in place, such as the plumbing stacks and mechanical shafts, we arranged them in a manner that allows for an open plan: the kitchen, bathrooms, and laundry closets are consolidated on the perimeter of the unit. These shifts allow for a more flexible floor plan.